An Urgent Conversation: AI and Librarianship

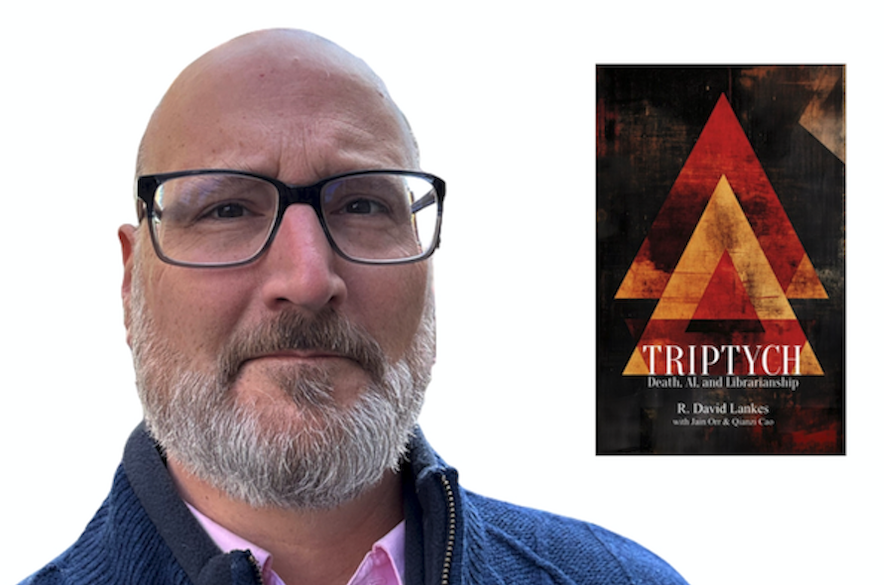

AI is a polarizing topic. But, in choosing to self-publish his new book, 'Triptych: Death, AI, and Librarianship,' library educator R. David Lankes hopes to accelerate a conversation about how the technology might help blunt a host of simmering crises in our communities, and in the profession.

I knew my new book, Triptych: Death, AI, and Librarianship was going to be different. I didn’t expect, however, it would become a sort of library AI Rorschach test. Like 14 years before when I wrote a self-published book that cited Wikipedia, a book that used AI in its production may be seen as a forward use of technology, or a capitulation to corporate greed.

Triptych is based on a series of ideas that I had been presenting over the past year on topics like AI, finding joy in a challenging time, librarians without formal degrees, and, perhaps most importantly, an intriguing term: “Deaths of Despair.”

The phrase “Deaths of Despair” was coined by two Princeton economists to describe why the life expectancy of middle-aged men (and later discovered in women) was declining for the first time in a century. It turns out that more middle-aged people were dying by suicide, drug overdoses, and complications of alcoholism against prevailing trends. When the economists sorted through the data looking for some common variables, they found that those who were dying, by and large, lacked four-year college degrees.

No, a college education doesn’t vaccinate people from suicide, alcoholism, nor drug abuse, the researchers acknowledged. But a four-year degree had come to signify greater wealth, and greater access to healthcare. And faced with a lack of control in the communities and society today, it seems that that a growing number of disenfranchised people had begun turning to things they believed would provide them relief.

So, I wrote Triptych to get the word out: libraries today need to shift from serving their communities—whether towns, colleges, schools, hospitals—and start saving them.

AI is not helping libraries with this mission—yet. But it might.

I understand how the message of the book may be somewhat blunted by the balkanization AI is prompting. But I believe that librarians must be knowledgeable about this revolutionary new technology. And I wrote the book with the help of AI because the best way to learn about AI's potential—positive and negative—is to engage with it, whether that engagement is aimed helping librarians save people from lives of despair, or to fight the potentially devastating effects of AI slop and the corporate disregard for the economic, cultural, and societal consequences of unleashing this powerful new technology before establishing any kind of safeguards.

Slow Science Requires Fast Publication

So, why choose to publish this book on my own, in partnership with Library Journal? Because time is of the essence.

I am a professor at a top-ranked global research university. As you can imagine, scholarship and publication are a big deal. Every faculty profile points to Google Scholar, making our citations a click away for anyone visiting the web.

Specifically, I study how communities and learning are at the center of librarianship and how we define a librarian. That has been the focus of my research for more than 15 years—and I’m not done yet. It is a very complex issue, and I have published several books on the topic, including The Atlas of New Librarianship in 2011 with MIT Press and the Association of Research and College Libraries, which won the 2012 ABC-CLIO/Greenwood Award for the Best Book in Library Literature.

That book and the subsequent books, articles, and conference papers aren’t the result of series of experiments. They are milestones along the way of a unified inquiry: I do interviews, I visit innovative libraries around the globe, I read and write and argue with peers and practitioners in the field. It is an example of action research.

For me, action research is not just a methodology, it’s a commitment to change through inquiry. It’s about engaging directly with the communities and systems I serve, identifying real world challenges, and collaboratively developing solutions that are both practical and transformative. My recent projects—such as a Dutch summer residency; working with 18 state libraries to evaluate AI tools; and ongoing community engagement—embody this ethos by prioritizing dialogue, reflection, and long-term transformation over rapid publication.

Like anyone who works in an academic setting, I have colleagues that publish multiple articles per year. They do so because their findings can have a big impact but are time sensitive. Many also do so because of the “publish or perish” academic norms that prioritize productivity and citations over larger social impact.

But, as any academic knows, traditional publishing is a slow process. It has accelerated in some fields with technology and the advent of open access and pre-print services like arXiv. But for many articles and books, the fact remains that by the time they are officially published they are essentially historical documents.

For this book, in talking about the potential for AI to save lives and to help library workers find joy in a time of book bans and an outright assault on knowledge organizations, the traditional publishing process wasn’t going to work. Input and conversation are needed now. Ironically, slow science requires rapid publication.

For example, in the book I talk about the dangers of a right-wing political effort to redefine library collections as government speech. To do that, I needed to include the a decision from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit that accepted that very line of reasoning. By choosing to publish the book myself, I was able to include the court’s latest decision, released in May, and still get the book distributed in June via print-on-demand, as well as in ebook and audiobook editions.

To be clear, I would not advise any of my non-tenured colleagues to take the path I have taken with this book. After all, one of the most important values of publishing with an academic press like MIT or Rowman & Littlefield (now part of Bloomsbury) is peer review. In scholarship, having an idea is fine but it is the scrutiny of fellow scholars that makes it research. Peer review is important. However, slow science sometimes leads to slow evaluation, and peer review often requires a longer runway.

For many topics, where the ideas are big but rarely fully formed, the traditional publishing model works well. For example, The Atlas of New Librarianship is, at its heart, a 400-plus page mind map that seeks to deconstruct the whole of librarianship and reassemble it with community partnership and learning at its core. That book needed both the authority of my publisher—MIT Press—and the expert editing, production, and marketing the press can provide. For a book exploring how various ideas of librarianship developed over 4,000 years, a two-year process wasn’t a problem.

While I am not publishing this book with a formal press, I am publishing it “in association with Library Journal.” What does “in association” mean? It means that LJ is interested in the content, is willing to experiment with other forms of publishing, and will provide marketing and publicity for the book through book excerpts, author interviews, and related webinars, which will draw subscribers and advertising dollars. It will drive attention, and conversation.

The bottom line is, as an established researcher, the advent of these new publishing tools affords me the chance to engage the professional community in a conversation as it develops. It is not unlike me writing this piece for Words & Money, an upstart in the library and publishing media world, and being told that there were not the kind of word limits or content restrictions that might exist for other magazines. We experiment, and we evolve.

To be clear, this doesn’t mean that I see traditional publishing as less valuable, or that I will always self-publish. As I see it, the purpose of scholarly publication is not so much the enshrining of truth, but to advance a conversation among scholars on a given topic. And when that scholarship requires immediacy, I will utilize self-publishing, when appropriate, as a tool to advance my work, even though that rapid turnaround may result in a few more typos and a few less conference booths.

What about the AI?

All that said, I admit that I do have concerns about some of the choices I made with this book. First and foremost, I worry that instead of focusing on the book’s message, saving lives from despair, the discourse will be more about artificial intelligence and its use in publishing.

Don’t get me wrong: I absolutely want to further the conversation about AI and librarianship. And as I wrote in the book, I understand that for some my use of AI in the illustrations and a bit in content (such as developing discussion questions at the end of sections, for example) is a deal breaker. And I respect that.

But let me explain why it isn’t a dealbreaker for me.

AI is rapidly becoming a divisive topic in librarianship. On one hand you have initiatives from ACRL claiming that AI literacy (broadly defined as the understanding and use of AI tool) is essential. And on the other hand, you have Violet B. Fox’s well thought out zine A Librarian Against AI.

Ignoring for a moment that AI in most cases is being flattened to mean only generative AI systems built by large corporations (Google, OpenAI, Meta, Microsoft…) trained on ethically dubious sources (such as collections of pirated books), I believe that AI literacy as an extension of Information Literacy is the wrong approach. Both AI literacy and information literacy revolve around a task model. That is, when someone is doing a task (looking for a site on the internet, reading up on the news, doom scrolling on social media) they somehow need to be prompted to become skeptical. That picture of the politician in suit and tie helping a hurricane victim wade through flood waters? Is that real? Is that AI? OK, time to bring out the CRAPP Test and be literate!

But what happens in an AI world where virtually every task generates doubt? AI slop, as it has become known, can be entertaining, deceptive, monetized, good or bad, but it all will have one certain effect on society: a degradation of trust in all media. And no question, AI has already begun to engender doubt in those we in libraries serve.

So, what does the life of a person look like when the AI built into their phone—as it is in both Android and iPhones today—makes it simple to adjust reality? With a few clicks and no training anyone can delete unwanted elements of a picture. Don’t like the radio tower in the background or the other tourist in front of the Coliseum? Click, they’re gone.

These tools can also easily add new elements to deceive. Got a funny picture of your brother? Great, now let’s add a line or two of cocaine!

With that in mind, it is absolutely fair and right to ask whether using my use of AI tools in this book is an endorsement of these tools? Quick answer: Yes, I am endorsing the use of these tools.

But I am not endorsing the use of these tools in all contexts and for all purposes. Rather, I believe if we are going to improve these tools, we need to know these tools. I believe if we are going to fight for our communities to mitigate AI’s potential harm—and the potential for harm is significant—we need to know how these tools work. And that means experimenting within the discipline to find a firm footing in a changing landscape.

Take Triptych is an example: it is a book written by a well known library scholar on an important topic: trust. As the author, because I want your trust, I am clear about the use of AI, stating it was for illustrations and other clearly delineated parts. Do you as the reader now now trust me, as the author? As you read the text, are you looking for traces generative AI? Triptych as a Rorschach test?

I know that sounds like I am trying to have it both ways and that I just made the case for the AI literacy efforts I just criticized. But bear with me.

When a person comes into a library for help, their life is already being influenced by AI. Their resume may have been rejected, not by a person, but an AI. They may have had an increase in their car insurance because an algorithm, not an actuary table, monitored their driving habits. On their way to the library they may have been surveilled by the city, or university, or local business, or their neighbor’s doorbell, all using AI to do threat prediction.

None of that is generative AI, of course, but all of that is AI. If we are going to truly help that person—and, harkening back to the conversation I would like to start with this book, potentially lengthen their lifespan by giving them greater power in the community—we need to understand and accept that AI is already in their phone, their watch, in their search results, their medical records, their social media feed, and yes, in their library’s collection.

Understanding that, it is not AI literacy but AI readiness that is needed. AI readiness is realizing that the work we do as librarians in the information field is no longer the intersection of information, people, and technology. Because technology is no longer a discreet factor, it is environmental. In that sense, moving toward AI readiness is not giving into the big theft, or the creativity killing, job eliminating, end-of-truth-corporate app. It is understanding how the lives of those we wish to serve—and, I would argue, save—function in this new environment.

Again, I understand this is not uncontroversial. In a recent study on AI readiness, my colleagues and I surveyed public librarians about AI, looking for librarians’ perceptions of AI in preparation for a series of focus groups. My favorite response was “Fuck UT [University of Texas] for asking these questions.”

Through the focus groups that followed, it became clear that some staff saw the university talking about AI as really the library inviting UT to train and implement AI in the library. In conversations with the staff we, the researchers, had to quickly clarify that AI readiness was not “ready to implement” or “ready to endorse,” but ready to discuss.

Among the staff, there were well-reasoned and passionate feelings on AI both positive and negative. Many saw AI—once again almost always defined as commercial generative AI systems—as just another tool, like Google search. Some saw it as a betrayal of the public mission of the library. Some saw it as a necessary and inevitable future. My colleagues and I. however, saw our task as preparing an organization like UT to talk about AI on a deeper level, so we can decide on its use or non-use from a place of knowledge.

To that end, I’ve also just finished up a year-long project to explore AI tools with 18 state libraries. We heard from experts, shared training, and thought together deeply on the dreams, dooms, and deconstructions of AI writ large.

Generally, most participants had a positive view of AI, though there was clear concern about the technology’s significant environmental impact, its propensity to hallucinate (in which AI systems present fabricated outputs as factual—think about the Chicago Sun-Times’ recent summer reading list), and yes, AI slop—the proliferation of low-quality often misleading AI-created content.

At the end of the project, I asked if the group wanted to make some combined statement, like IFLA had. The response was no. Becoming more educated on the tools, trying the tools, experimenting and talking with their communities didn’t need to lead to some inevitable endorsement or common frame, the group concluded. Our purpose was to give people more information to make better local decisions. And each of the participating libraries would have their own take.

It's Not Coming, It’s Here

Here's what also became clear in our work with the state libraries: Generative AI is disrupting education and publishing NOW. From the third-grade leaf collection to the doctoral dissertation, AI is already in broad use.

What’s more, professors like me have little idea how to evaluate critical thinking skills in the social sciences without summarization and writing—which happens to be about the easiest thing for Generative AI to produce. It would be lovely if we could just say “don’t use it.” But an AI prompt is literally sitting next to every line I write in Microsoft Word, and it waits for me in Google Docs. And I am not convinced that pen and paper and blue books and a locked classroom is an equitable way to assess the writing skills and critical thinking of students, many of whom whose first language is not English.

And in publishing? I mentioned that centrality of peer review to scholarship That process has shown its fatal flaw. The flaw is not in the ability for a reviewer to discern AI generated texts from those written by human hand. It is in the ability of a human being to process thousands and thousands of manuscripts when they used to be reviewing only ten or twenty submissions.

All of which leads back to the core of AI readiness as an alternative approach to AI literacy. Readiness is not achieved by building up the skill of the individual, but in building up trust within a community.

For example, AI slop stops when people reject shady social media accounts en masse. Peer review still works in academic communities, but because a person’s reputation is more important than their productivity. And when you write a book with AI images, you declare it, and explain why you made that decision. Not to bring everyone to agreement, but to enter a conversation honestly.

As a scholar, as an author, as a librarian, and in my personal life, I use AI tools. My car can drive itself. My watch is monitoring my health. My phone makes my crappy photos better. And I enjoy transforming words into pictures with Photoshop and with Midjourney.

Do I have concerns? Yes. I am worried about the environmental impacts of AI. But I also know that new chips and new algorithms are reducing the energy consumption of AI, just as happened at the dawn of internet search. I also know that AI has been used to improve the energy efficiency of transportation systems and management of the energy grid.

Am I concerned about the use of creators’ work in the training of generative AI systems? Somewhat, but not as much as you might think.

Do some of these statements make me a hypocrite? Probably, yes. But I have studied the knowledge infrastructure that librarians help steward for too long to find any hard truths.

Dealing with complexity and compromise are central to anyone who seeks to be of service and to promote the greatest good: Google revolutionized document delivery in reference and it skews its results to favor paying customers. Facebook allows people to connect and deploys an army of engineers to monopolize my attention. Elsevier makes science available to more researchers more efficiently and demands extraordinary rents to buy back our own content. And now, we have AI—which is amazing and horrible all at once.

But what I hope to do—in my work, with this essay, and with the publication of Triptych: Death, AI, and Librarianship—is to think about AI, study it, experiment with it, and hopefully facilitate an honest conversation that can help maximize results in terms of the lives we in libraries can help improve.

R. David Lankes is the Virginia & Charles Bowden Professor of Librarianship at the iSchool at University of Texas at Austin.