Anthropic, Authors Strike Tentative Settlement Deal in AI Copyright Suit. But Will It Be Approved?

The deal looms as a potential milestone in the development of AI. But with tensions running hot between authors and the tech industry, lawyers say that getting a final deal approved may prove challenging.

In a potentially major development, lawyers for AI company Anthropic and a recently certified class of book authors have struck a potential deal to settle copyright infringement claims stemming from the company’s unauthorized downloading of millions of books from several online pirate sites. But despite news of the settlement—the details of which have not yet been made public—lawyers tell Words & Money that getting the settlement across the finish line may not be a slam dunk.

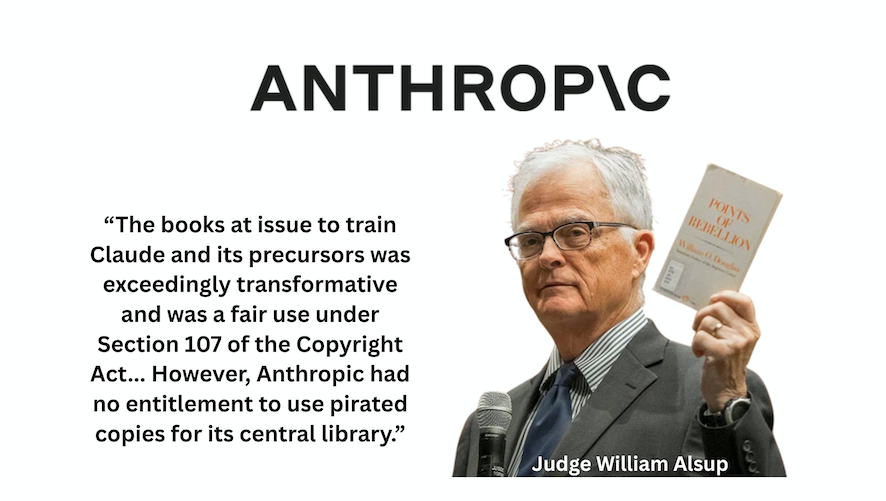

News of the deal comes after judge William Alsup, in a mixed summary judgment decision in Bartz et al v. Anthropic PBC, found that Anthropic's unauthorized use of copyrighted books to train its Claude AI system was fair use. But the judge also found that the company's decision to keep millions of unauthorized downloads for a permanent "central" research library was not.

“The use of the books at issue to train Claude and its precursors was exceedingly transformative and was a fair use under Section 107 of the Copyright Act,” Alsup explained in his June 23 decision. “However, Anthropic had no entitlement to use pirated copies for its central library,” the judge wrote, ordering the company to stand trial on that claim.

Weeks later, on July 17, Alsup racheted up the pressure on Anthropic by certifying a potentially massive class of authors and rightsholders—reportedly covering up to seven million books downloaded from pirate sites—putting the company on the hook for potentially billions in damages, and ultimately leading to the proposed settlement.

Details of the proposed deal should be available next week. In an August 26 order, Alsup set a September 5 deadline for the parties to begin the preliminary approval process for the proposed deal, with a hearing set for September 8.

What's in the Deal?

With dozens of lawsuits currently challenging the legality of using unauthorized works in AI training, the class action deal looms as a potential milestone in the development of AI. But the approval process for class action lawsuits can be complicated, the lawyers told Words & Money, and getting to a final, court-approved settlement in this case could be challenging. As always, the devil will be in the details.

“It will be fascinating to see how this plays out, because at this point the only live issue in the case is the use of shadow libraries as data sources,” says Brandon Butler, executive director of the Re:Create coalition, a pro-fair use copyright group. Could the parties seek to expand the prospective settlement beyond the narrow issue of Anthropic using unauthorized downloads to create a permanent research library? Perhaps, Butler concedes. After all, despite winning on its fair use for AI training claims at the district court, the legal battle over AI training is far from over, and Anthropic would certainly benefit from having authors in this settlement agree to some kind of release for training purposes in exchange for payment. Furthermore, authors could also benefit from a broader deal: for example, authors who sign a release for AI training might be able to secure bigger payouts.

But such an expansion would also come with risk. Class action law requires that the court hear objections and ultimately determine that any final settlement is “fair, reasonable, and adequate,” before approving it. And with tensions running high between copyright holders and the tech industry, a more expansive proposal that includes some kind of permission structure or a proposal not deemed to be sufficiently punitive for Anthropic's piracy could “inflame dissenting class members,” Butler notes, and expose the settlement to more—and more vocal—objectors.

“If the settlement ends up being narrowly tailored to the shadow library issue, which would please judge Alsup and avoid angering dissenting authors, it could move more quickly,” Butler observes. “If they try to cover more territory, it could get messy.”

Cornell Tech law professor James Grimmelmann agrees.

"The unknowns are the scope of the release and how much Anthropic can do with the books and models, the size of the payments, and whether there will be enough seriously dissenting authors objecting through skilled counsel or otherwise opting out in a way that could derail the settlement,” Grimmelmann told Words & Money. In that respect, Grimmelmann suggests it would make sense for the parties to keep the proposed settlement more narrowly focused on the pirated library copies.

“We lived through this with the Google Books and Muchnick settlements, which took years,” he points out. “If this settlement is just or primarily about the downloads, it will be smaller, less controversial, and much less complex.” And, he adds, echoing Butler's observation, it could move much faster to final approval.

“I wouldn't be surprised if Anthropic feels it can bear the risk of continued litigation over AI training but is willing to make a payment in line with what Alsup might be likely to order for failure to pay for the books it downloaded,” Grimmelmann explains. “The company will have to deal with authors of other kinds of training data and it will always have to worry about infringing outputs, but what it really needs right now is to put behind it the massive legal risk of statutory damages from its shadow library downloads, which is very much a one-off legal risk that it can avoid incurring again.”

Shades of Google

As Grimmelmann suggests, the demise of the Google Settlement in 2013 still stings for many in the publishing and author communities. And it stands as a warning.

In that case, which involved Google’s scanning of library books to create an online index, the parties attempted to settle an intractable copyright dispute by leveraging it into a sweeping new digital marketplace, replete with a commercial offering to libraries and a so-called “Book Rights Registry.” But after three contentious years, Judge Denny Chin, citing a wide array of more than 6,800 objectors—including the U.S. Government—found that the settlement simply went too far, and rejected it.

The “Muchnick” settlement, meanwhile, also known by the shorthand Freelance, took more than a decade to conclude, including two trips to the Supreme Court. When it was finally approved in 2014, the deal, which was capped at $18 million, marked the culmination of nearly 20 years of litigation that began with the landmark digital rights case Tasini vs. New York Times. And when the checks finally went out in 2018, writers collected just under $9.5 million, a little over half of the funds set aside for the settlement.

Multiple lawyers agreed that the Anthropic case is significantly different than the Google case. But there is at least one common denominator between the two cases: strong opinions.

“I think we can safely assume there will be dissent from virtually any proposal given the wildly divergent opinions about AI training among authors and publishers,” Butler says. “I’d expect the more fair use friendly authors to dissent to the extent that the settlement might imply that AI training requires a license. And you’ll see some authors dissenting because they don’t want to participate in an AI licensing regime by another name. A narrow settlement could possibly avoid this. But I do question whether the parties could be satisfied with a narrow settlement."

The proposed settlement will also need to comply with the law, and there are significant questions about whether the massive class—which was very swiftly approved by Alsup—is workable.

On August 7, prior to the settlement announcement, several groups including the Authors Alliance, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Association of Research Libraries, the American Library Association, and Public Knowledge, filed an amicus brief with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in support of Anthropic’s bid to appeal Alsup’s class certification.

“Class certification is important in this case because it means that the plaintiffs who brought the suit now have the ability to legally represent, and potentially bind, class members who are not present,” David Hansen, executive director of the Authors Alliance, wrote in a recent blog post. “Many Authors Alliance members are likely members of this class. We have a particular interest in ensuring that the views of those authors who are supportive of fair use, open access, and wide dissemination and use of their works are not co-opted by rights holders who have opposing views.”

Specifically, reps for the Authors Alliance—which was formed in the wake of the Google Settlement—question whether such a massive, proposed class of authors as approved by Alsup, with “such a diversity of interests” can satisfy the “commonality” requirement necessary in class action litigation.

“Astonishingly, the district court certified this class with…no analysis of what types of books are included in the class, who authored them, what kinds of licenses are likely to apply to those works, what the rights holders’ interests might be, or whether they are likely to support the class representatives’ positions,” Hansen explained in blog post. “Had the district court conducted such an analysis, it would have uncovered decades of research, multiple bills in Congress, and numerous studies from the U.S. Copyright Office attempting to address the challenges of determining rights across a vast number of books. It would have revealed how the complexity of years of publishing contracts makes ownership determinations fraught and prone to conflict. It also would have shown that rightsholders have genuine and significant differences of opinion about the legality of AI and the specific uses Anthropic has engaged in.”

In a competing brief, the Authors Guild, along with the International Thriller Writers, the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association, and the Romance Writers of America, argued that the class Alsup approved is appropriate and lawful.

"We emphasize that because most of the pirated works are recently published ebooks, publishers and rightsholders can be readily identified through copyright registration data, ISBN/ASIN numbers, and standard industry records," reps for the Authors Guild wrote in an August 22 blog post. "Far from being unworkable, the class process provides a practical and efficient way to address infringement on such an enormous scale."

Whether any potential class deficiencies are enough to sink the settlement remains an open question. At the very least, if approved, administering the final settlement might prove difficult, lawyers suggest. But once again, that will come down to what’s in the actual settlement proposal.

Another potential wrinkle: Will the Trump administration decide to wade into the settlement process, and if so, how?

Notably, the U.S. Copyright Office lacks leadership at the moment after the firing of Register of Copyrights Shira Perlmutter. But before her firing, the Copyright Office had issued a three-part report that voiced concern over the use of pirated works for AI training.

"In the Office’s view, the knowing use of a dataset that consists of pirated or illegally accessed works should weigh against fair use without being determinative," the Copyright Office report notes. "Copyright owners have a right to control access to their works, even if someone seeks to obtain them in order to make a fair use. Gaining unlawful access therefore bears on the character of the use."

But in its AI action plan released in July, the Trump administration ignored the copyright concerns of creators. And in his own remarks, Trump appeared to contradict the Copyright Office's guidance.

"You can’t be expected to have a successful AI program when every single article, book or anything else that you’ve read or studied, you’re supposed to pay for,” Trump told attendees at an event in Washington, D.C. last month. “You just can’t do it, because it’s not doable.”

Once more, the devil will be in the details of the settlement.

"The DOJ’s opposition to the Google settlement was surely driven by the Copyright Office, which is probably not as capable of pushing an agenda inside the administration right now," Butler told Words & Money. "I would suspect that the administration’s AI czar David Sacks would advise not getting in the way of a settlement if he thinks it’s in the broad interest of the AI sector in the U.S."

Expectations

There is also a question of managing expectations. In an August 27 post, the Authors Guild noted that the lawyers representing the authors (who also represent the Authors Guild in their class action lawsuit against OpenAI) agreed with the decision "to settle on a fair and favorable basis" rather than to litigate the Anthropic case for years. “We hope this sends a strong message to the AI industry that there are serious consequences when they pirate authors’ works to train their AI," added guild CEO Mary Rasenberger.

Butler, meanwhile, voices a different concern with the settlement. "If the settlement is approved, it means we won’t get an answer in this case to the important question of whether an otherwise fair user can be attacked because of the source of their data," he says, fearing the settlement might "overshadow Alsup’s ruling in favor of fair use for AI training. "The settlement will be otherwise benign if it is limited to the shadow libraries claim, and if the damages bear some reasonable resemblance to the lost revenue that plaintiffs can allege based on those lost sales," he says.

Meanwhile, with dozens more lawsuits over AI training still in the pipeline, Grimmelmann, is taking the long view.

"One step at a time," he says. "Copyright is never going to provide all the answers to major social debates like AI. But if this settlement helps to lock in the idea that AI training is allowed on works that were acquired legitimately, that could be a positive development in the space. Copyright owners could license to provide convenient, legitimate access, while those who object to such training could opt out and withhold their works. That seems healthy."