Are Library Book Decisions Government Speech? After Controversial Fifth Circuit Decision, a Florida Judge Is Now Set to Weigh In

After a summary judgment hearing, judge Carlos E. Mendoza is likely to be the first judge to weigh in on whether library book decisions are government speech since the Fifth Circuit's May 23 ruling.

After a May 22 hearing, a federal judge in Florida is now set to rule in one of the nation’s most closely watched book banning lawsuits—a publisher-led challenge to two provisions of HB 1069, the 2023 Florida state law that opponents say has led to hundreds of books being pulled from Florida public school libraries.

But after a shock ruling last month by the Fifth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals in another lawsuit over book banning, a key question in the case has taken on added importance: Are library book decisions “government speech” and thus immune from First Amendment challenges?

First filed in August 2024 by six major publishers, the Authors Guild, and a coalition of students, parents, and several bestselling authors, the suit seeks two declaratory judgments: one, that HB 1069’s sweeping prohibition on “sexual content” in K-12 schools is unconstitutionally overbroad; and, two, a ruling that that the law’s use of the term "pornographic" is synonymous with the state’s existing "harmful to minors" standard, which is properly grounded in the Supreme Court's time-tested standard for obscenity as set forth in Miller v. California. Or, if the court finds that’s not the case, a ruling that the ill-defined term is unconstitutionally vague.

Central to the case, the plaintiffs note the state has created a mandatory form for schools to evaluate content that has separate categories for “pornographic content” and for content that's “harmful to minors,” suggesting that the terms are not synonymous in the state’s view, and that books are being banned as "pornographic” under the statute even though they are not obscene under Miller.

In their motion for summary judgment, the plaintiffs note that the two challenged provisions of HB 1069 have caused librarians and educators to self-censor in the face of potentially harsh penalties for noncompliance, which has led to hundreds of books being improperly pulled from school and classroom libraries in the state, including classics like Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings and Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, as well as books by the named plaintiff authors—Julia Alvarez, Laurie Halse Anderson, John Green, Jodi Picoult, and Angie Thomas.

“Because there are few, if any, obscene books in school libraries, the many unconstitutional applications of the Challenged Provisions substantially outweigh its constitutional applications,” the plaintiffs argue. “The Challenged Provisions bar all consideration of context, prohibiting local school librarians from exercising their professional judgment and constricting, rather than empowering, parental choice. Neither the value of the book nor a student’s readiness and desire to read it count for anything. If the First Amendment has any force in public schools, the Challenged Provisions must be declared unconstitutional.”

In its defense, the state is banking largely on technical legal arguments—including that the plaintiffs lack the standing to pursue their claims. Notably, the judge in the case, Carlos E. Mendoza, has already rejected those arguments in denying the state’s motion to dismiss.

But on the merits, state attorneys argue that administrators have near total discretion to choose which books the school library can provide access to, including whether to provide a library at all.

In their motion for summary judgment, state attorneys characterize school libraries as a “gratuitous benefit” that the state is under no obligation to provide or maintain. And to the extent that the state does provide access to a school library, “the curation of school library books is government speech,” they argue, and thus not subject to First Amendment challenges.

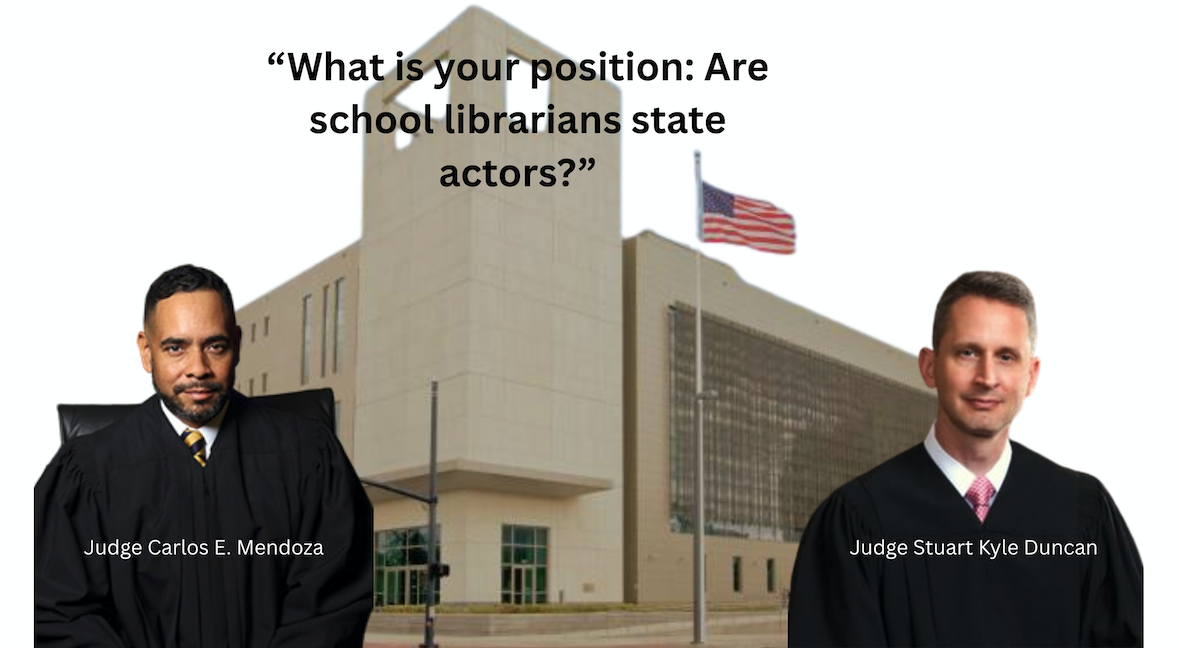

At a summary judgment hearing on May 22—a day before the Fifth Circuit delivered its bombshell decision in Little v. Llano County—Mendoza opened by suggesting that the government speech issue, along with the issue of prudential standing, would be “determinative.” And as state attorney Jason J. Muehlhoff prepared to present his argument, the judge jumped right in.

“I just have a question to open up with. What is your position: Are school librarians state actors?” Mendoza asked.

“Excuse me, your honor?” Muehlhoff responded.

“Are school librarians state actors?” Mendoza repeated.

“I would believe so, your honor, yes.” Muehlhoff responded. “The state is speaking through its decisions on how to edit and curate the library books that it puts in its libraries... Collecting independent third-party speech is a form of speech itself. And once that's established, the question is: who is speaking? The government, private citizens, or somebody else? And, here, under the government speech framework, we think it's clear that it is the state speaking.”

The Fifth Circuit Aftermath

On background, lawyers question whether Mendoza’s decision will in fact turn on the question of government speech. Among the more interesting arguments to arise at the May 22 hearing, for example, was the question of how closely book offerings in school libraries are tied to curricular decisions.

But the government speech question stretches well beyond the litigation in Florida. Since 2021, it has animated a surge in book banning policies and legislation in several states. And all eyes are now on Mendoza, as he will likely be the first judge to weigh in on whether library book decisions are government speech since seven judges of the Fifth Circuit endorsed that idea in its May 23 decision.

In a filing just hours after the Fifth Circuit delivered its opinion, Florida state attorneys made sure Mendoza was aware of the ruling.

“[Little v. Llano County] supplements State Defendants’ government speech argument made in their summary judgment papers,” asserts a notice of supplemental authority filed by the state, specifically citing the Fifth Circuit’s majority opinion’s holding that “a library’s collection decisions are government speech and therefore not subject to Free Speech challenge.”

In a June 4 filing, however, the plaintiffs rejected the state’s characterization. “Contrary to the State Defendants’ contention, the Fifth Circuit’s decision in Little v. Llano County does not supplement the ‘government speech argument made in their summary judgment,’” the plaintiffs told the court, noting that only seven of 17 judges joined the section of the majority opinion concerning government speech. “No court has ever held that library book removal decisions are government speech. Little did not change that.”

Furthermore, the Fifth Circuit’s extraordinary finding that there is no First Amendment right to receive information with regard to library books runs afoul of numerous other court decisions, the plaintiffs point out—including in the Eleventh Circuit, which has authority over Mendoza’s Florida district.

In essence, the government speech doctrine holds that when the government speaks, it is free to say what it wants without restraint under the First Amendment. Think about a plaque on a monument, for example.

Historically, courts have narrowly and cautiously defined the bounds of what constitutes government speech, given the extraordinary implications of waiving First Amendment protections. And, as the plaintiffs suggest in their filings, the right-wing movement to sweep in library book decisions would be a dramatic expansion of the government speech doctrine—and one with potentially major implications for our democracy. Want to ban every book about race or the LGBTQ community from your local public or school library? Perfectly acceptable, conservative lawyers in several states have argued. If your community doesn’t like it, their solution is at the ballot box, not the courts.

So far, that expansive view of the government speech doctrine has not been widely embraced by the courts. Several judges have held that libraries are meant to collect a diverse array of books to serve the entire community, not just to serve a majority of voters in any given election cycle, and recognized that giving politicians nearly unfettered power to erase people, subjects, and ideas they don’t approve of would radically transform libraries from engines of inquiry and education into mouthpieces for the state.

In July 2023, judge Timothy L. Brooks, an Obama appointee, eviscerated the state’s government speech argument in his decision to strike down key parts of Arkansas’s Act 372. “By virtue of its mission to provide the citizenry with access to a wide array of information, viewpoints, and content, the public library is decidedly not the state’s creature,” Brooks concluded, “it is the people’s.”

In January 2024, judge T. Kent Wetherell—a Trump appointee—also expressed skepticism in his decision to allow another publisher-led lawsuit over book bans in Escambia County, Florida, to proceed. “The Court simply fails to see how any reasonable person would view the contents of the school library (or any library for that matter) as the government’s endorsement of the views expressed in the books on the library’s shelves," Wetherell wrote in his opinion.

And, in August 2024, in its review of yet another publisher-led lawsuit seeking to block the book banning provision of Iowa’s SF 496, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit expressly rejected the idea that the government speaks through the books school librarians and educators choose to make available.

"It is doubtful that the public would view the placement and removal of books in public school libraries" as the government speaking, the court held, observing that a well-appointed school library might include copies of Plato’s The Republic, Machiavelli’s The Prince, Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan, Karl Marx and Freidrich Engels’ Das Kapital, Adolph Hitler’s Mein Kampf, and Alexis de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America.” If placing these books on the shelves of public school libraries constitutes government speech, the court concluded, then “the State 'is babbling prodigiously and incoherently.'"

But then came the Fifth Circuit. In its May 23 decision, the court reversed its own three-decade unanimous holding in Campbell v. St. Tammany Parish School Board, a 1995 First Amendment decision involving the attempted removal of a book from a public school library that has long served as an anti-censorship bulwark for librarians. In his majority opinion, conservative judge Stuart Kyle Duncan, a Trump appointee, held that there is no right to receive information in publicly funded libraries and proclaimed the Eighth Circuit’s view that library book decisions are not government speech to be wrong.

In Duncan’s view, library book decisions are akin to a government endorsement. “What the library is saying is: ‘We think these books are worth reading,’” Duncan wrote—a view that librarians strenuously reject. “The library is not babbling incoherently in the voices of Captain Ahab, Hester Prynne, Odysseus, Raskolnikov, and Ignatius J. Reilly,” Duncan concluded. “Rather, the library speaks by selecting some books over others and presenting that collection to the public.”

Widely considered to be the most conservative court in the land, the Fifth Circuit’s decision sets up a high stakes showdown at the Supreme Court—at some point. But first, judge Carlos Mendoza will have an opportunity to respond to the Fifth Circuit’s findings.

Is the Fifth Circuit decision a right-wing outlier? Does it suggest a shift in how the government views libraries and the First Amendment? While Mendoza is not bound by the Fifth Circuit decision, whether—or perhaps how—it plays in his ruling will certainly be instructive.

A Landmark?

Not to be overshadowed by the Fifth Circuit’s government speech drama, the outcome in Mendoza’s court—however it is decided and on what grounds—will be a major decision in its own right.

Enacted in 2023, HB 1069 is a cornerstone of an ambitious conservative agenda in the state of Florida that has national ambitions. Between 2021 and 2023 Florida lawmakers have passed several state laws billed as part of a so-called parental rights agenda. And in a joint report from PEN America and the Florida Freedom to Read Project issued this week, advocates cautioned that legislation like Florida’s HB 1069 are not “common sense” measures to protect students, but Trojan Horses designed to “empower a vocal and censorship-minded minority.”

“Since 2021, the Sunshine State has led the country in advancing the ‘parental rights’ agenda. Contrary to its name, this agenda has used fuzzy, coded language to manufacture moral panic, and to deliver control over what students can read and learn in schools not into the hands of all parents but to a particular segment of citizens,” the report states. “With the advent of the second Trump Administration, the country now faces the prospect that Florida’s approach to public education will become a blueprint for federal policy.”

In filing its suit to block HB 1069, the major publishers leading the suit acknowledged the case's importance.

“Fighting unconstitutional legislation in Florida and across the country is an urgent priority," the publishers said in a joint statement announcing the suit last August. "We are unwavering in our support for educators, librarians, students, authors, readers—everyone deserves access to books and stories that show different perspectives and viewpoints.”