Court Wipes Out Florida's ‘Overbroad’ Book Banning Law

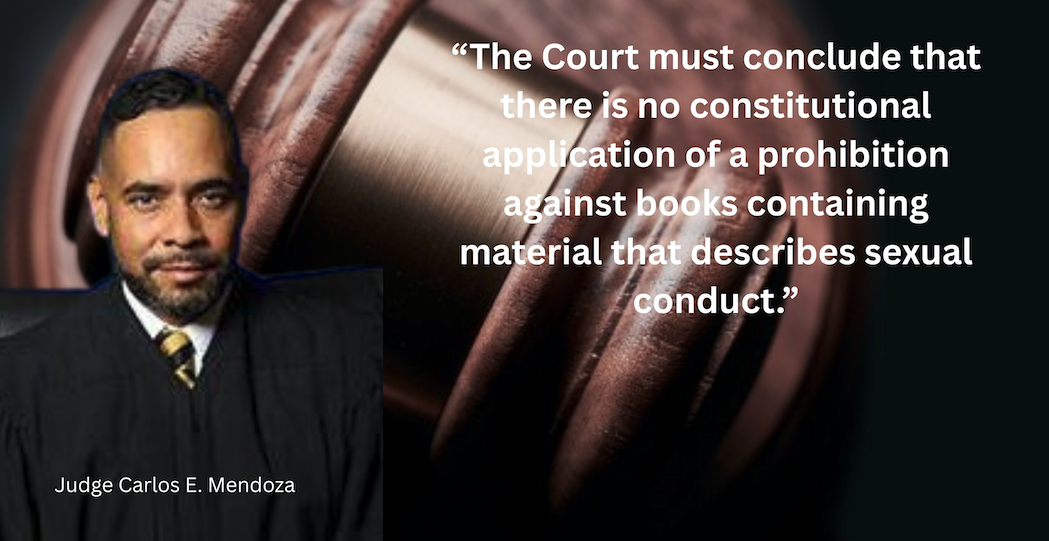

In a massive win for the freedom to read, judge Carlos E. Mendoza on August 13 found Florida state law HB 1069’s blanket ban on any materials that describe sexual content in school libraries to be unconstitutional.

In one of the nation’s most closely watched book banning lawsuits, a federal judge has effectively struck down a sweeping prohibition on books containing sexual content in Florida schools.

Delivering a massive win for the freedom to read, judge Carlos E. Mendoza on August 13 found Florida state law HB 1069’s blanket prohibition on materials that describe sexual content in school libraries to be unconstitutional, and further declared that the statute’s use of the vague term “pornographic” must be read as synonymous with the state’s existing definition of “harmful to minors,” which is properly grounded in the Supreme Court’s standard for determining obscenity as set forth in the landmark 1973 case Miller v. California.

Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed H.B. 1069 into law in May 2023 as part of a suite of bills that defined his so-called "Let Kids Be Kids" agenda. Critics, however, quickly pointed out that the new law’s vague language was creating a climate of fear and uncertainty among school librarians and administrators and leading to hundreds of books, including dozens of classic works, being summarily pulled from Florida school libraries in order to avoid potential prosecution, civil penalties, or other professional consequences.

In August 2024, a coalition of plaintiffs led by six major publishers, the Authors Guild, several bestselling authors, and a group of parents, sued the state and two counties (Orange and Volusia) challenging two provisions of HB 1069 which the plaintiffs say has led to sweeping book bans across the state.

In the suit, the plaintiffs argued that that HB 1069’s ban on books and materials that describe sexual content is unconstitutionally vague and overbroad. Mendoza agreed, and in the opening lines of the decision affirmed that a student's right to receive information in a school library is protected by the First Amendment.

“By enacting HB 1069, the Florida legislature sought to prohibit material from entering or remaining in school libraries that is not obscene for minors,” the judge concluded. Before HB 1069, Mendoza noted, books that describe sexual conduct were “evaluated in their entirety in relation to the age and maturity of students who may read it” using a “Miller-for-minors test” that is already “baked into” Florida law. Given that obscene material is already prohibited in schools under Florida law, HB 1069 clearly targets "non-obscene material,” Mendoza reasoned, tipping the law's applications “into those barred by the First Amendment.”

In his thorough 50-page decision, Mendoza pointed to “unrebutted” evidence that Florida schools are not, in fact, awash in inappropriate content.

Citing several declarations, Mendoza said there was significant evidence establishing that “non-obscene books have been removed from public school libraries to the dismay of students that deeply identify with these books.” At the same time, Mendoza said the defendants failed to identify any "obscene books that have been removed" under the law.

Furthermore, the evidence showed that HB 1069’s ban on sexual content has left librarians and educators to grapple with “vague and ambiguous statutory language” under the threat of serious penalties—even though they have not encountered “a single piece” of obscene content.

“It is unclear what the statute actually prohibits,” Mendoza observed. “It might forbid material that states characters ‘spent the night together’ or ‘made love.’ Perhaps not. Defendants do not attempt to explain how the statute should work.”

Which, of course, may be the point of the law’s provisions, Mendoza suggested. After all, the vagueness of HB 1069’s prohibitions, the judge noted, only served to expand their sweep.

Exacerbating the situation, Mendoza pointed out that the Florida Department of Education has directed educators to “err on the side of caution,” which, as the plaintiffs argue, has led school librarians and officials to “err on the side of removing books” based on “fear that they and their school districts” will face punishment.

Indeed, that very situation has been in the headlines recently, after state officials publicly flogged school administrators in Hillsborough County for not moving swiftly enough to ban 55 books on a state-created list. In an August 7 statement, PEN America Florida Director William Johnson said teachers and librarians in Florida have been “operating under a cloud of anxiety and fear.”

To be clear, banning content under Florida’s existing “harmful to minors” law is “plainly a constitutional application,” Mendoza added, because that existing law explicitly incorporates a defined, constitutionally sound “Miller-for-minors standard.” With HB 1069, however, there is no definition for what constitutes “sexual content” or may be considered “pornographic.”

“By leaving these items undefined, Florida has given parents license to object to materials under an ‘I know it when I see it’ approach,” Mendoza wrote, adding that there is a reason the Supreme Court rejected that standard for defining obscenity. “The Court must conclude that there is no constitutional application of a prohibition against books containing material that describes sexual conduct.”

In terms of the second challenged provision—HB 1069’s ban on “pornographic” materials, particularly as used in a state-generated evaluation form which lists “pornographic” as a reason for removing a book—Mendoza accepted the plaintiffs’ cleverly presented invitation: Rather than undertake the more legally complex, “strong medicine” of declaring the provision facially invalid, the plaintiffs suggested the court could, in the alternative, simply declare that the term “pornographic” as used in HB 1069 is synonymous with the state’s existing—and properly defined—obscenity standard, which the plaintiffs agreed is lawful.

Mendoza thus granted summary judgment for the plaintiffs on that basis, and denied the alternative motion to strike the provision.

“The reading prescribed by the Objection Form unmoors the word ‘pornographic’ from any context and expands its scope into unconstitutional applications,” Mendoza concluded, suggesting that he could also have found the provision unconstitutional, if necessary. But a declaration that holds “pornographic” to be synonymous with “harmful to minors” under Florida law means that the law’s prohibition against “pornographic” content “can be constitutionally applied,” the judge ruled.

Government Speech?

For their part, the defense mainly presented technical legal arguments, including challenges pertaining to standing. Notably, the court had already rejected those arguments when it denied the state’s motion to dismiss, and easily dispatched with them again.

But Mendoza also rejected the state’s core defense on the merits—that school library collections are “government speech” and thus immune to First Amendment scrutiny.

Florida's government speech argument stretches beyond the litigation in Florida, as it is the legal argument animating the ongoing surge in book banning policies and legislation in several states. And after a shock decision in May by the Fifth Circuit court of appeals in a closely watched book banning case from Texas, Little v. Llano County, all eyes have been on Mendoza, as the first judge to weigh in on the government speech argument in libraries since the Fifth Circuit decision.

In essence, the government speech doctrine holds that when the government speaks, it is free to say what it wants without restraint under the First Amendment. Think about the text of a plaque on a monument, for example.

Historically, courts have narrowly and cautiously defined the bounds of what constitutes government speech, given the extraordinary implications of waiving First Amendment protections. But in recent years, right wing activists have sought to expand the government speech doctrine to cover library book decisions. Since libraries are funded by taxpayers, the argument goes, the decisions made by librarians about what books to offer in a library is an expression of the government, and thus not open to a First Amendment challenge.

Want to ban every book about race or the LGBTQ community from your local public or school library? Perfectly acceptable, conservative lawyers in several states have argued. If your community doesn’t like it, the solution is at the ballot box, not the courts.

So far, until the Fifth Circuit, the idea of expanding the government speech doctrine to library collection deciusions has largely been rejected by the courts. In several cases, including challenges in Texas, Iowa, and Arkansas, judges have held that libraries are meant to collect a diverse array of books and recognized that giving politicians nearly unfettered power to erase people, subjects, and ideas they don’t approve of would radically transform libraries from engines of inquiry into mere mouthpieces for the state.

In his decision this week, Mendoza added his name to those skeptical of the government speech argument.

“Defendants frame this case broadly as the government curating the selection of books in the library and argue that is government speech. That is problematic for two reasons. First, it is unclear whether, even under that broad umbrella, this would constitute government speech. And second, Defendants’ framing ignores the narrower reality of the statutory scheme at issue here,” Mendoza wrote.

In approaching Florida's government speech argument, Mendoza quickly differentiated the Florida case from the Fifth Circuit case in Texas, in which a plurality of the court held that libraries curate their collections for “expressive” purposes.”

“Here, the government is not engaging in expressive activity. Despite Defendant’s best efforts to frame it as such, the statutory provision at issue does not involve discretion of government employees in curating an appropriate collection of library books,” Mendoza wrote. “The statute here mandates the removal of books that contain even a single reference to the prohibited subject matter, regardless of the holistic value of the book individually or as part of a larger collection. Moreover, many removals at issue here are the objecting parents’ speech, not the government’s.”

Furthermore, “it is unclear what the government seeks to express by allowing a book to be removed on the given statutory grounds without any consideration of the book’s holistic value,” Mendoza held. “Defendants cite no case law for the proposition that the government may impose a blanket prohibition on non-obscene material in school—or even public—libraries.”

In fact, applying the factors of the Supreme Court’s “holistic” Shurtleff test for government speech, case law cuts against government speech, Mendoza held.

“Historically, librarians curate their collections based on their sound discretion not based on decrees from on high,” the judge wrote. “A blanket content-based prohibition on materials, rather than one based on individualized curation, hardly expresses any intentional government message at all. Slapping the label of government speech on book removals only serves to stifle the disfavored viewpoints. That way, the Supreme Court has warned, lies danger.”

Next Steps

At press time, it was unclear how quickly the ruling might provide relief for Florida librarians and educators, or whether banned books would soon be returning to school library shelves in Florida.

In a statement, Jason Muehlhoff, chief deputy solicitor general in Florida Attorney General James Uthmeier's office, called the ruling "a bad decision" and said the state would appeal.

On Bluesky, reps for the grassroots Florida Freedom to Read Project said members were still processing what it called a "seismic" win.

"The judge’s order makes it clear that we cannot judge a book by its cover or a maliciously selected excerpt out of context. This means that the thousands of books that have been prohibited from student access without careful consideration of their value should be returned to shelves immediately," the post continues. "While we fully expect an appeal, we encourage state leaders to think about future civics lessons and whether or not they will be on the right side of history arguing against the rights of its citizens."

When we started FFTRP during the 21/22 SY, we were hoping our research efforts would lead to a ruling (or law) that would affirm students’ First Amendment rights. While we expect an appeal, the judge’s 50-page order offers freedom strong footing. www.wuwf.org/florida-news...

— Florida Freedom to Read Project (@flfreedomread.bsky.social) 2025-08-14T10:46:01.381Z

In a statement, ALA president Sam Helmick also celebrated the win. "This victory is a result of Floridians coming together in support of libraries—parents, students, and friends of the library are willing to stand up against censorship," Helmick said.

First filed On August 29, 2024 in the Middle District of Florida, in Orlando, the plaintiffs include all of the Big Five Publishers (Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, Penguin Random House, and Simon & Schuster along with Sourcebooks, a majority of which is owned by PRH) along with the Authors Guild, a coalition of parents, and authors Julia Alvarez, Laurie Halse Anderson, John Green, Jodi Picoult, and Angie Thomas.

Penguin Random House associate general counsel Dan Novack called the decision a "sweeping victory for the right to read," and for every student’s freedom "to think, learn, and explore ideas."

“The Court ruled that books may only be removed from school libraries if they lack serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value when considered as a whole," Novack said. "We are especially heartened that the Court rejected the State’s dangerous claim that the First Amendment does not apply in school libraries. The Court also struck down the State’s vague 'I know it when I see it' standard, reinforcing the essential role of librarians and educators in selecting books for students’ independent reading."