In Conversation: Journalist and Author Vauhini Vara

In her latest book, 'Searches: Selfhood in the Digital Age,' Vara delivers a potent, highly engaging exploration of AI, technology, and humanness.

The AI arms race continues to heat up, day by day. Last month, two major decisions were handed down among dozens of court cases grappling with the rollout of the technology. Just this week, Nvidia, whose chips are powering the AI revolution, became the first company to hit a $4 trillion evalution. And with the Trump Administration expected to release a report on AI sometime this month, the stakes are likely to grow even higher.

In January, author and journalist Vauhini Vara gave the closing keynote at the American Library Association's LibLearnX Conference in Phoenix. And like the rest of the room, I listened with rapt attention as she spoke about her interactions with AI and other technologies, her experimental 2021 short story “Ghosts,” in which she used an early version of ChatGPT to write about her sister, who died from a rare form of cancer, and her new book Searches: Selfhood in the Digital Age. What I heard that day in Phoenix blew away my ill-formed, headline-influenced notions of how to approach not only AI, but my own agency and creativity.

With Searches, Vara weaves memoir, journalism, and her interactions with technology to create a potent, singular meditation on humanity. It's a must read for anyone seeking to grasp the power of technology (or more to the point, the power of technology companies) beyond the current discussions of AI's economics, or the lawsuits.

I recently caught up with Vara to talk about Searches, the rise of AI, and what it means to be human.

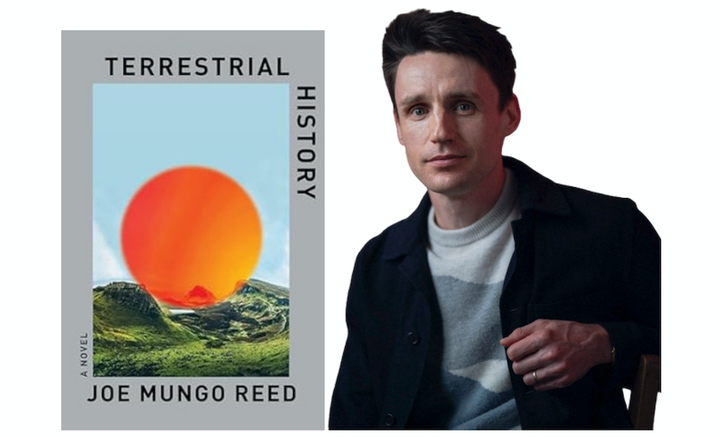

I’ve had the pleasure of seeing you speak a couple of times now, at the LibLearnX meeting in January in Phoenix, and at your reading in New York in April. Both were excellent talks. In New York, which was a conversation with your friend and Stanford University classmate, author Tony Tulathimutte, I thought it was funny how Tony just kind of launched into a discussion about AI before realizing he hadn’t let you tell people about your book first. So before I do the same, let me back up and give you a chance to tell us a little bit about Searches.

Vauhini Vara: It's interesting, because I believe strongly that any book is a kind of co-creation by an author and a reader, because a book can be different to everyone who reads it. But something that has struck me with this book, as I’ve heard from people who have read it, is how very different people's readings are. In some ways, it makes me want to resist questions about what the book is, because I find there to be something really important about so many people taking different things from the book.

At the same time, it would be disingenuous of me not to admit that that part of me wants to say, ‘Hey everyone, I wrote the book because was really interested in the idea of complicity and the ways in which it's impossible to critique big tech companies and their products without also casting that critique inward.’ With Searches, I was really trying to encompass that dual critique, and to put forth the idea that there is not necessarily a clear boundary between them—that is, Big Tech—and us. And I came upon an approach that combines fairly conventional journalistic and memoir narratives with more experimental forms to explore how those two critiques are necessarily intertwined.

As a writer and publisher who's been trying to get my head around the potential impacts of generative AI, Searches really hit the mark, because of the way you structured the narrative and because of how you, as a journalist and fiction writer, engage with technology. But the book's format is pretty experimental. So, I'm curious to know how you felt while you were writing the book, and now that it’s out there and has received some strong reviews, how you feel about it now?

I think this might be my best book. I’ve always been a journalist and a creative writer, but those two parts of my identity always felt kind of felt separate. And the thing that I found exciting about writing this book is that it felt like a way to bring those forms together. I think I found a form with this book that allowed me to be a little subversive, and to offer a critique on the level of form itself.

At your talk in New York, you told the audience that you have both an aversion to and a curiosity with AI—which I think a lot of us can relate to. But you said it was the aversion that drove you to write the book. Can you explain that?

Yeah, for me, aversion drives curiosity. It's not that like there's aversion on one hand and curiosity on the other—they're actually bound up with each other. I don't think of this book as being a book about AI, I think of it as being a book about big technology companies and their exploitation of us and our complicity in that exploitation. So, when I talk about curiosity and aversion, for me that applies to my use of all these companies’ products, not just AI, and my intellectual curiosity around the fact that I know that I am being exploited by these big corporations, but at the same time I am actively engaging in that exploitation without anybody putting a gun to my head.

Tony kicked off your conversation in New York by sort of flippantly stating that he thinks AI is from hell and that no one should be using it for any reason. Do you agree, and did you hear a lot of comments like that on your tour?

Tony expressed his feelings most strongly of everyone I've engaged with about the book. But one thing that has surprised me is that some readers have been reading the AI-related material and my engagement with AI as if it's meant to show something positive or neutral about AI. It’s not.

What I was trying to do with this book was to engage with AI in a way that I hoped would show how AI is a tool of big technology corporations aiming to consolidate their power and wealth. So anytime AI shows up in the book—at least in my reading—that is what it's showing.

Now, as I said before, readers are of course allowed to have their own readings and opinions. I like that. But just to be clear, I intended this book to be a critique. I don't agree with the arguments advanced by these big technology companies that AI was designed to benefit us. So, I admit that it feels a little uncomfortable to me that some readings of the book have described it as even-handed, or that I talk about the concerns around AI but that I also consider how AI could be good for us. That was not my intention.

I've written a lot about tech disruption in the publishing industry over my career and, to hear some tell it, books and libraries were supposed to be dead or at least irrelevant by now. They’re not, of course. Far from it, I'd argue. But it does feels like the potential for disruption from AI is on a whole other plane. I'm curious how you see AI in relation to the challenges that the tech industry has brought to writers and publishers in recent decades?

I see AI as a continuation of this path that we've been on, in which big technology companies are encroaching upon humanness and exploiting it for their own purposes. I do think AI is an acceleration. But to characterize it as something new I think leads us to put the focus on this sort of humans vs. the machines argument, in which we position people against this technology, when in reality, I think the more relevant threat here is from the big technology companies, which have been expanding their power and wealth for decades now. I think understanding and focusing on that structural dynamic is much more important.

The primary way the publishing industry has been confronting AI thus far is mostly the same playbook the industry has used for confronting Big Tech in the past—mostly by suing for copyright infringement. I understand that argument. But it’s not lost on me that this is the same losing argument that was made against Google for scanning books, and given the massive implications of AI, I question whether licensing and copyright are the right tools for the job now at hand. Do you have any thoughts on this?

Oh yes, I have a lot of thoughts on this. I'd say that, while I’m sure the Big Five publishing companies have literary values in mind, we have to remember that they too are large corporations beholden to shareholders and investors. So financial outcomes are going to be important to them. For entities that represent authors and creators, like the Authors Guild, for example, my sense is that they're most interested in agency on the part of individual authors. And so they end up taking the stance that authors should be able to make individual choices about how they want to approach AI. They’re focused on questions of consent and compensation. But I agree there is a bigger, more complicated picture here.

In the book I describe a potential future in which big technology companies do start asking for consent and offering compensation, and that becomes a part of the AI ecosystem. But as these companies train their models and their models get better, eventually that consent and compensation for artists ends up not mattering anymore, because the big technology companies are eventually able to generate and monetize all this AI content on their own. Ultimately, there will no longer be a human antecedent that needs to be compensated for AI training. There will have been a generation of human artists that were compensated. And that’s it. I think that's one very plausible future if we go in this direction of prioritizing consent and compensation.

That potential outcome seems very clear and obvious to me. So why then do you think so much of the resistance to AI is bound up with copyright and licenses and getting big tech to pay money in the short term, when that outcome would still not address the bigger threat of machines taking over the work of human artistic creation?

I’m not entirely sure, but I think publishing companies and organizations representing artists may not believe that all the writing, images, music, and video that we produce today is actually defensible from AI training. Maybe some of it. But certainly not all of it. Probably not even most of it. And so, if these big technology companies have the capacity to build this technology regardless, why not at least try to get a piece of the pie? This is especially true if governments, whether the U.S. government or the Chinese government or any other, believe that this technology is important for staying economically competitive, or for national security. If that’s what’s happening, then maybe the agency of artists really is limited, right?

At this stage, I think everybody is kind of just feeling their way around. But as you can probably tell from reading the book, I really do believe strongly in the possibility for change driven by individual and collective agency. And I do think that there is a world in which the people say no, this is not the future that we want. And that’s how we keep that future from coming about. I mean, it’s happened before. There are all kinds of technologies and products that people just rejected and so we don't have them. Nobody wanted research into human cloning, for example, and so we don't really do that. There are a number of sectors where, collectively, we’ve made the decision not to pursue certain things. I think it's possible for this to be one of them.

That’s fascinating, because I remember thinking after a presentation this year at the London Book Fair that no one is really clamoring for authorless books, or AI bands, or virtual movie stars. At the same time—and this actually came up during the Q&A at your reading in New York—there does seem to be a belief that AI will augment artistic output. For example, one person at your reading talked about her mother writing a memoir using AI because English isn’t her first language. So, there are positive outcomes here, aren’t there?

I would disagree with that, actually. As I write in the book, there are subtle dangers involved that are difficult to perceive in using these products as aids in self-expression. I gave the example in the book of my dad using ChatGPT to edit his emails and his emails becoming infused with American English because ChatGPT removed the Indian English that is so closely associated with his identity. I think that's an unambiguously negative thing. For me, that’s a major point my book is making—that there is only superficial benefit here at best and that it comes with real harm.

I thought the last chapter of the book was especially engaging. I won’t spoil the ending for those who haven't read the book yet, but it is based on a Google survey asking people a series of questions and collecting their responses to questions revolving around the question “what it is like to be alive?” Explain the purpose that chapter serves in the book?

In my view, the book is an argument for human curiosity, creativity, and self-expression, and an argument for finding ways to push back against the totalizing influence of big technology companies and their products. I think the question underlying the book is, to what extent can we do that within the structures these companies have built? Or, to use Audre Lord's concept, as I do in the book, to what extent can we use the master's tools to break down the master's house?

Now, I don't think the book is as interested in answering the question as much as it is in raising it. I would argue that what makes human expression important isn't that some of us get to make money by publishing books that are in libraries and bookstores, it's that all of us have the capacity to use language in totally original ways that reflect our perspectives, our position in the world, our understanding of the world itself, our perception of who we are, and who we are communicating with.

So, to the extent that I see my book as one big argument to counter the totalizing rhetoric of big tech companies as expressed by their CEOs and as contained within their products, giving the last chapter to actual human people speaking in their own voices about who they are and what interests them, that just felt like the most apt ending for the book.

You’re a journalist. An acclaimed fiction writer. And you’ve delved deeply into AI and the influence of Big Tech. I’m curious what about what you’ll do next—and how tech might feature in your next creation?

I am currently working on a play adaptation of Ghosts that I've been working on for a while, and I am also working on a new novel that does have to do with AI. In both cases, I continue to be interested in looking at the power and wealth behind AI.