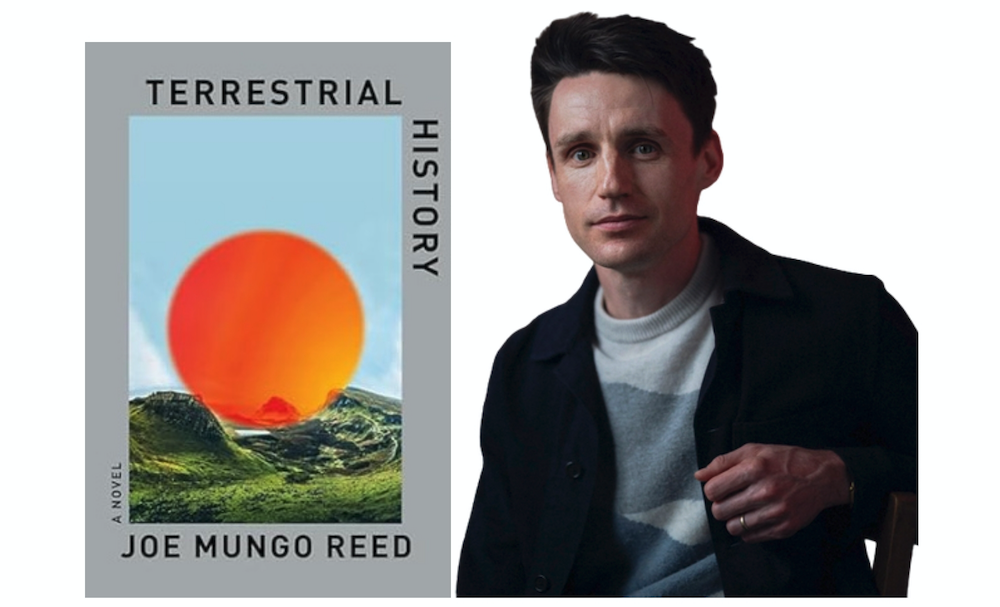

In Conversation: Novelist Joe Mungo Reed

Words & Money catches up with the author, whose latest book, 'Terrestrial History,' has landed on several 'best of' lists from public libraries, and earned a place on the longlist for the 2026 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction.

In their year-end selections for Best Books of 2025, both the New York Public Library and Chicago Public Library selected author Joe Mungo Reed's novel Terrestrial History. The American Library Association has also selected the novel for the 2026 longlist of the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction. Words & Money recently caught up with Reed to talk about his novel, and why he values libraries and librarians.

Your new book, Terrestrial History, came out earlier this year. Can you tell us a little about the book and what inspired it?

I started the book during the holiday season a few years ago. I always enjoy that time of year, because it’s the one time when my academic responsibilities really fall away. I generally use the time to do a lot of reading. And I recall that, in the winter that I started to plan Terrestrial History, I had just read Mark O’Connell’s book, Notes from an Apocalypse. There’s a section in that book that details how difficult Mars colonization would actually be, and from that inspiration I started to imagine the perspective of a child who had been born into a limited, depressing space colony without ever knowing Earth. I imagined a family tree stretching behind this child, imagined the history that might lead back to Earth.

Early on, I work in images, and I remember coming up with the idea of a machine-like creature rising out of the sea, and that became the first major event of the novel. Of the three books that I’ve written, this one has stayed closest to my initial vision. I’d call it a family saga that takes us from the present day, via four generations, to a space colony early in the next century.

What do you hope readers take away from the book?

In one respect, this book has a pretty obvious political slant. I don’t think that the narrative leaves the reader with any doubt that I as an author feel that abandoning the fight against the climate crisis to fly off to space is a dumb idea.

Having said that, I didn’t want the narrative to serve merely as an articulation of one position. I hope that at a more detailed level, one that acknowledges that the earth getting hotter is a bad thing, the reader doesn’t find themselves steered too neatly towards answers. I have characters who want to solve the climate crisis via social and political solutions and others who believe in technological fixes. Some characters are political idealists, and some are pragmatists. My intention was to explore these differences in approach without fully endorsing any of them. Alas, I don’t have a blueprint for saving the world, but if I did a novel probably wouldn’t be a venue for such a thing anyway! What I wanted the book to capture is the emotional side of things: we know where we want to get to, but not how to get there, and the process of muddling out this how is wrenching, especially when we disagree with those close to us.

Terrestrial History was selected by the New York Public Library and the Chicago Public Library as one of their Best Books of the Year, and it has been longlisted for ALA's Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence. What does it mean to you to have librarians celebrate the book the way they have?

I couldn’t be more thrilled. I’m working in a crowded field. There’s a lot of very good dystopian novels coming out right now, understandably, and so to have librarians, who due to their vocation read so widely and deeply, picking my book out as noteworthy is hugely flattering.

I’m also a writer who doesn’t mind the term "literary." I know that the term has its baggage, in terms of implying a certain mannered style, maybe, overlooking genre, perhaps connoting navel-gazing. Yet if one thinks of the term more loosely, perhaps merely as an indication that the writing tries to attend to the fine detail of the world, then I’m glad to take it on. I don’t actually know the reading sensibilities of librarians, or even whether they could be said to have common sensibilities! But I’m just going to project wildly, and say they seem like discerning readers. If my book rewards their careful scrutiny, I’m overjoyed.

Did libraries play a role in the writing of Terrestrial History, for research, writing, etc.?

Research was very important in the writing of this book. This isn’t a novel that goes into the technological detail of space travel in the way that writers like Andy Weir or Kim Stanley Robinson do, yet I did need to understand enough about how we might live on Mars to feel that my fictional vision was cohesive. Libraries were an important venue for this work, especially as I was often cherry-picking sections of books to answer specific questions, like, what is wind like on Mars?

Working at the University of Cambridge, I’m very lucky to be part of an institution that has over 50 libraries. There’s always a book somewhere in the network that answers one’s question, no matter how arcane. I also think that process is very important. Some of my students now use chatbots in researching their fiction, but not in their writing, so they promise, yet I think that this approach has the deficiency of precluding incidental discoveries. If a machine just gives you a concise answer, you miss the journey towards that fact and the things you stumble over en route.

At one point my wonderful editor, Nneoma Amadi-obi, pointed out that I needed to do more to explain nuclear fusion, which features in Terrestrial History, to the reader, so it was back to the books to learn more about that process for myself! Along the way, I remember learning that when scientists initiate a fusion reaction the center of that reaction becomes the hottest place in our universe. I thought that that was an amazing fact that illustrated the difficulty of stabilizing fusion reactions, so it went in the book.

In terms of my writing, libraries are my preferred place to work when outside my home office. I love finding a secluded table amidst the stacks. I firmly believe that books can only be written with the use of other books. There’s something inspiring about working surrounded by books. When you’re in the middle of writing a book the very endeavor itself can seem perverse and foolish. To be able to look up at the stacks and see row upon row of completed books, to consider all of the people who have endorsed the importance of literature by writing all those pages, is heartening.

Do you have any words you'd like to share with librarians who might be interested in adding Terrestrial History to their collection, or suggest it to readers?

Of everything I’ve written, this book has definitely precipitated the strongest reactions from readers. I hope that that’s a result of addressing timely, urgent issues.

I also feel proud of the characters in the novel. There are four main protagonists, and the novel is structured in alternating chapters told from the perspectives of these protagonists. I’ve been interested and gratified that different readers have found themselves taken with different characters. The youngest character, Roban, the boy in the Mars colony who I referred to earlier, has an earnest sensibility very much at odds with the wry, world-weary perspective of his great grandmother, who readers meet in other sections. Hopefully, this variation makes space for a range of readers to find points of identification in the narrative.