Internet Archive, Music Labels Settle Copyright Suit

The settlement appears to be the last gasp of a contentious, years-long copyright battle that began with a lawsuit over book scanning in the early days of the pandemic.

The Internet Archive's five year copyright infringement odyssey appears to have finally reached a crescendo, with the organization announcing this week that it has reached a deal with a coalition of major music labels to settle copyright infringement claims over its program to preserve vintage 78 rpm recordings.

The settlement was announced in a court filing on September 12, and confirmed by Internet Archive officials in a blog post on September 15, although terms of the settlement were not disclosed. "The parties have reached a confidential resolution of all claims and will have no further public comment on this matter," IA officials said in the post.

The lawsuit was first filed on August 11, 2023 by a group of major record labels, following a consent judgment to settle copyright infringement claims after the Internet Archive lost a lawsuit with several major publishers over the scanning and lending of library books. While the financial terms of the publisher settlement were not disclosed, the Association of American Publishers said the payment “substantially” (but not fully) covered the publishers’ “significant attorney’s fees and costs” in bringing the case.

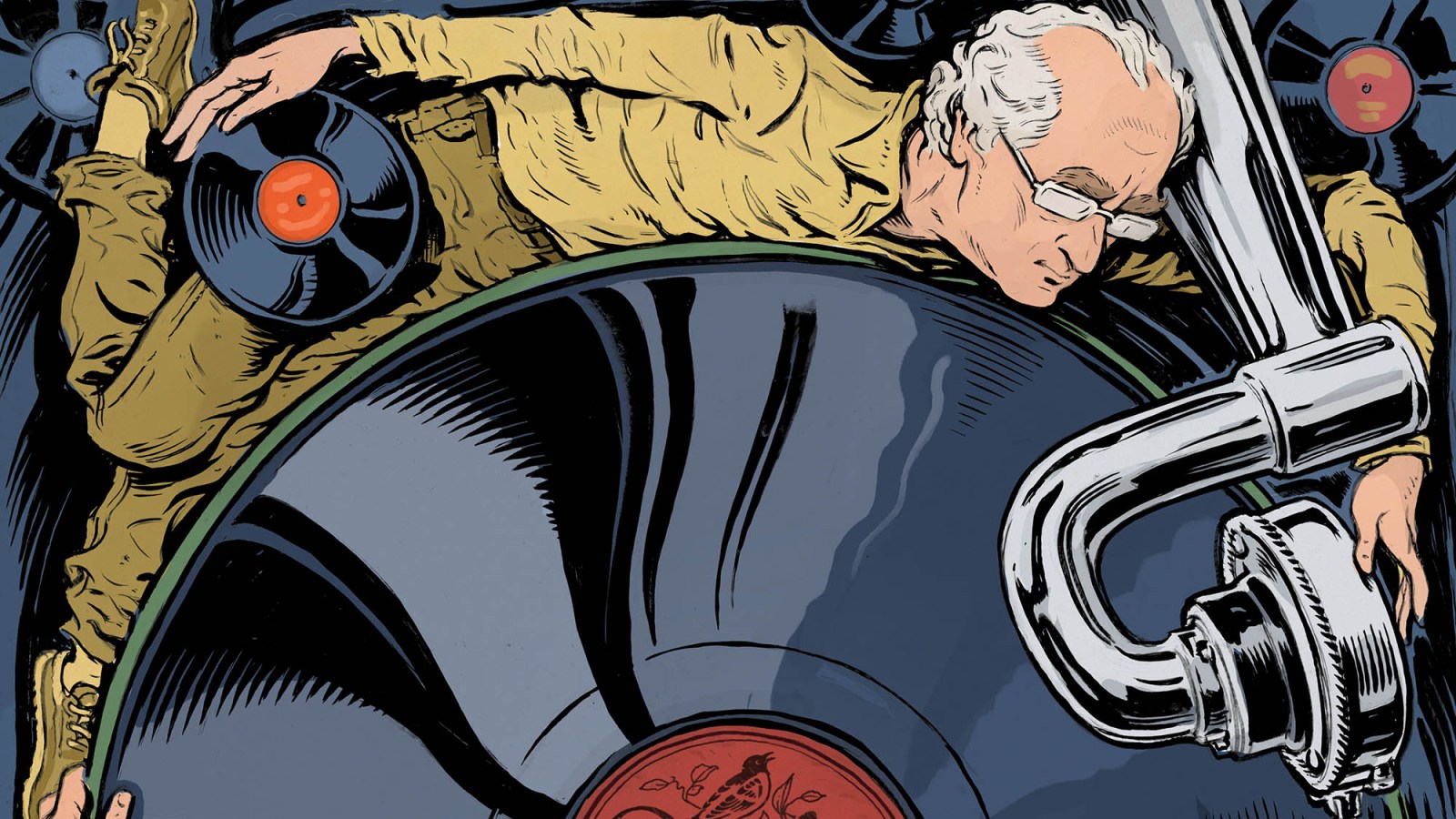

But in their suit, which cited the publisher case, the record labels claimed the Internet Archive’s "Great 78" program, which, with the help of audio preservationist George Blood, facilitated the digitization of tens of thousands of obscure, endangered 20th-century 78 RPM and made them available to users for free, amounted to industrial scale copyright infringement and reportedly sought more than $600 million in damages—an existential threat to the Internet Archive.

In a September 2024 article in Rolling Stone, writer Jon Blistein took a deep dive into the Internet Archive's mission, and the lawsuit.

"If you want to explore the old, weird expanses of recorded-sound history, there’s no better resource than the Great 78 Project," Blistein wrote. "Click around, filter by year, genre, language, and you’ll find an infinite scroll of discs—most issued by long-defunct labels like Victor, Vocalion, Edison, Oriole, Okeh, and Brunswick— their front labels photographed and laid out in a grid, each one leading to a web page with a straight rip of the crackly recording. A folk, blues, or country tune, a lost jazz gem or minor big-band hit, a Yiddish comedy bit, Hungarian opera, Argentine tango, polka, foxtrot, gospel, hymns, or even just the sound of a person laughing because that’s what people wanted to hear when it became possible to record a human voice."

Blood, who was also named as a defendant in the lawsuit, told Rolling Stone that the program's aim was the “preservation of the cultural record,” and noted that "95% or more" of the records in the collection were not available anywhere and were in danger of being "lost to time.”

The End of an Era?

The settlement appears to be the last gasp of a contentious, years-long copyright battle that began in the early days of the pandemic, when the Internet Archive announced that it was temporarily removing lending restrictions on the books in its Open Library initiative for a program called the National Emergency Library. The program was aimed at students whose access to books was curbed during the Covid-19 lockdowns.

The move outraged publishers, however, who had long bristled over the Internet Archive's scanning and lending program, and a lawsuit was filed on June 1, 2020, in the Southern District of New York by Hachette, HarperCollins, Penguin Random House, and Wiley, organized by the Association of American Publishers. The suit challenged not only the National Emergency Library but the concept of "controlled digital lending," at the time a legally untested theory at the foundation of the Internet Archive's scanning and lending program.

In a press release announcing the suit, AAP executives said the Internet Archive’s program was an attempt “to bludgeon the legal framework that governs copyright investments and transactions in the modern world,” and compared it to the “largest known book pirate sites in the world.”

In a separate statement, Authors Guild president Douglas Preston said the IA program was “no different than heaving a brick through a grocery store window and handing out the food—and then congratulating itself for providing a public service.”

And on March 24, 2023, judge John G. Koeltl, delivered an emphatic summary judgment ruling in favor of the plaintiff publishers. In September 2024, a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit unanimously affirmed Koeltl's decision.

“At bottom, IA’s fair use defense rests on the notion that lawfully acquiring a copyrighted print book entitles the recipient to make an unauthorized copy and distribute it in place of the print book, so long as it does not simultaneously lend the print book,” Koeltl wrote in his opinion granting the publisher plaintiffs’ motion for summary judgment and denying the Internet Archive’s cross-motion. “But no case or legal principle supports that notion. Every authority points the other direction.”

In the wake of the lawsuits, the Open Library program remains, but thousands of copyrighted books have since been removed. And while the settlement with the music labels suggests an end to the legal wrangling may be in sight, librarians say the fundamental problem that led to the dispute in both cases remains: namely, that the work of libraries and the preservation of our cultural heritage is under threat in a digital age where works cannot be owned, but only licensed.

In a July 23, 2020 press conference, in the early days of the litigation, Internet Archive founder Brewster Kahle laid out his view:

“The publishers are saying, in the digital world, [libraries] cannot buy books anymore. We can only license them, and under their terms. We can only preserve them in ways that they have granted explicit permission for, and only for as long as they’ve given permission," Kahle said. "And, we cannot lend what we’ve paid for, because we don’t own it."