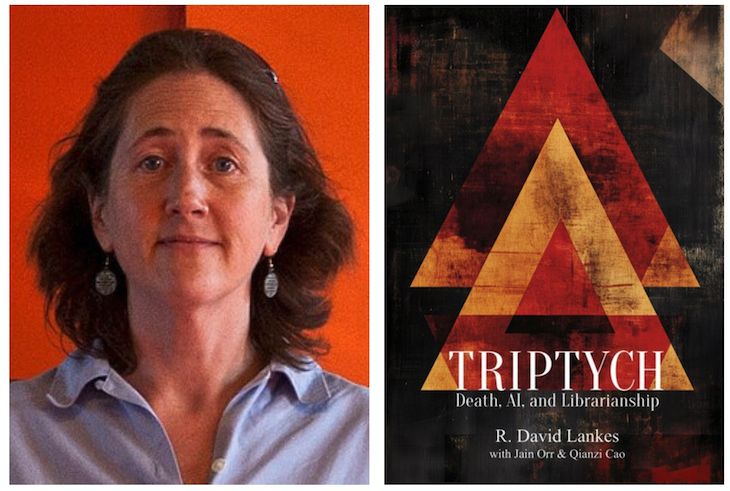

Jessamyn West on 'Triptych: Death, AI, and Librarianship' by R. David Lankes

Libraries don't just change lives, they can save them, concludes R. David Lankes in his new book. Can AI play a role in that mission?

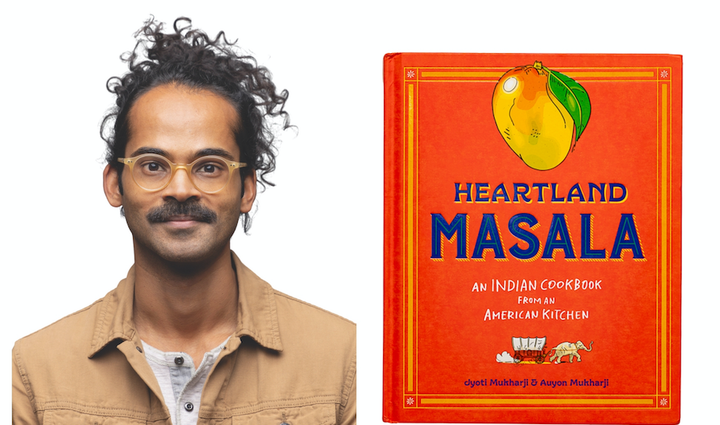

Triptych: Death, AI, and Librarianship by R. David Lankes with Jain Orr & Qianzi Cao.

I've read and enjoyed books by R. David Lankes before. I believe he brings good food for thought to the table when we mull over the complex philosophy and the practice of librarianship. His opinions are not uncontroversial, and I appreciate that. I suspect he is an engaging professor.

But I raised an eyebrow when I got to the "I used artificial intelligence (AI) to help me write this book" part of the introduction to his new book, Triptych: Death, AI, and Librarianship, which he self-published at the end of June “in association with Library Journal,” which is running a series of excerpts from the book.

Since AI was mentioned in the title I should not have been surprised. For what it's worth, I did not use AI to help me write this review.

I am an AI skeptic. By that I mean that I’m someone who would prefer to see more mammogram use cases and fewer "Kermit if he was a goth, drawn in the style of Basquiat" use cases. I think all the major AI companies at this point in time are exploitative and extractive, and I can't foresee a future where this is not the case.

That may be a failure of imagination on my part, I admit. I pay a lot of attention to what Hugging Face is up to. And I feel that even calling large language models "AI" cedes territory that is very much still disputed.

However, I also work with people and technology enough to understand that the use of LLMs and other AI tools has very much become normative. For me, to not try to understand how people are using these tools, or dismissing them out of hand, would be like refusing to use any popular tool that Other People Like (Microsoft Teams, Canva, my state's bespoke ILL software). It would close off part my knowledge of what's going on.

I am also a born copy editor. I'm not bragging—it's actually not a great default setting. But it's mine, and I do my best with it. But I was 11 pages into an ARC of the book—which is more a collection of linked essays than one cohesive narrative—and I'd already found several typos, a lot of ‘this isn't English’ phraseology, odd capitalization choices, and writing style issues. Not the usual AI tells, but this took me out of the narrative. A simple example, which I hope will be fixed in the final edit, is the use of the phrase “TL; DR” with a space between the first and second part. If you write out the phrase "too long; didn't read" there's a space. The acronym has no space.

I get that the typos could very well be fixed before the book is published (ARCs typically warn against quoting from early versions for this very reason). And, of course, I know with certitude what was meant. So, does this ultimately matter?

I'm not sure. I wonder whether my distraction with these issues in the book stem from a subliminal desire to find to find AI tells in the writing. I've read several of Lankes' previous books; I even assigned one of them for a class I taught. This sort of thing was not present in those books. It was distracting in this one, as was that weird sheen of the book’s AI-generated images.

At the same time, I feel that way a lot lately. These feelings are, I believe, a new part of the human condition, and sitting with them was an unexpected and interesting part of engaging with this book.

A professor at the University of Texas, Lankes does the academic thing and spends a fair amount of time defining his terms. He explains, for example, what he means by the word "librarian," and what he means by the word "community." Overall, the text feels directed more toward early career folks who might benefit from a refresher on some of the building blocks of the profession. I did not mind the "just play the hits" recounting of these concepts (though I missed a nod to my pal Ranganathan).

He also uses terms of art like “feral librarian” (Jim Neal's term to describe librarians without formal training) and “deaths of despair” (which was coined by economists and pertains to the excess mortality that aligns with hopelessness). When he discusses how libraries are "always owned by the community" it seems clear that he is referring to public and possibly school libraries, but that is not explicit.

Lankes has also been to the Netherlands recently and like many librarians before him he was inspired by what he found there. His reflections on that experience, including as a chapter titled "Hi, I’m the Problem It’s Me," made for lively reading.

Among his major points, Lankes argues that libraries need to take a more proactive stance in addressing the current crises in their communities in an active, rather than a passive, model of service. This includes standing up to book banning, for example, moving past the outmoded idea of neutrality, and working against the loneliness epidemic which is expanded on and critiqued briefly in some supplemental materials at the end.

He also suggests that AI is inevitable and we ignore it at our peril. AI will make people trust—or distrust—information in new and different ways that we as library workers need to understand more fully than we do, he argues. We should embrace these options and explore them joyfully with our communities. I was expecting this section to be much longer, and was actually relieved at its brevity.

Lankes writes about why librarianship is more about being on board with the values and the mission of the work (with a nod to “vocational awe” and its pitfalls) than the degree. And he doesn't shy away from talking about ALA accreditation of library education programs and what that can mean in states where right wing political attacks on the ALA have developed in recent years. I appreciated his willingness to look at this issue head on.

These sections all ended with "conversation starters" which will be familiar to anyone who has ever read a book club book. ChatGPT came up with those. They seemed fine.

Lankes' writing is at its best when it's slightly confrontational, telling you why something won't work or that it's the wrong approach. I know he's a cheery guy, so this doesn't come with the crank vibes that other library critics may give off. I inwardly cringed when he recounted a story of a local mental health initiative that didn't work. My cringe wasn't because the initiative wasn't good, however, but because the well-meaning non-library people who wanted libraries to apply for grants to do more work didn't grok how that wasn't appealing to already under-resourced libraries. We've all seen and can relate to that sort of problem.

Lankes' also talks about industrialized libraries and the sort of smoothing out of local library practices (Sandy Berman, I see you) in order to achieve economies of scale and lower-cost solutions to doing more with less. He also discusses and postulates about the possibilities of post-industrialized libraries which can return to focusing on their communities and doing what works for them. He stops short of saying that libraries have lost their way. But, in some ways, haven't we?

Above all, Lankes imparts a sense of urgency. Libraries don't just change lives, he posits, they can save them. But to do that, they will have to change, and soon.

The idea is not new, of course. But the sense of urgency he brings is. Lankes urges librarians to focus on empathy and community, to think past the degree or the job to become "librarians of spirit" who rush toward the burning building that is the sometimes unbearable awfulness that is America in 2025: We're here, we can help, we can do it together.

Jessamyn West is a nationally known speaker, writer, library technologist, and educator on the issues facing today’s libraries. She is based in Orange County Vermont.