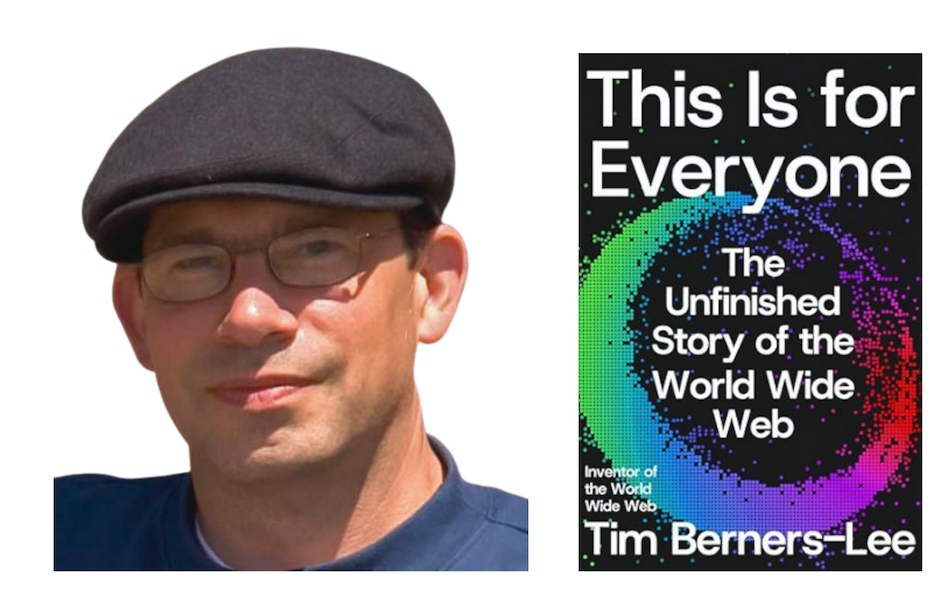

Peter Brantley on ‘This Is for Everyone: The Unfinished Story of the World Wide Web’ by Tim Berners-Lee

"In this age of increasingly rich and powerful tech companies, Berners-Lee’s vision for the web remains fundamentally democratic," writes Peter Brantley. "That everyone, anywhere, with access to what is now known as the internet, should have the ability to create and share information freely."

This Is for Everyone: The Unfinished Story of the World Wide Web by Tim Berners-Lee (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2025).

The first browser that I ever used was called ViolaWWW. This was in the early 1990s, when I worked at the University of California San Francisco Library and Center for Knowledge Management (CKM), where I became tangentially involved in litigation over new “plugin” functionality for an early browser developed by CKM staff and subsequently patented by UCSF. Eventually, these early web patents were overturned, based in part on testimony provided by none other than Tim Berners-Lee (aka TBL), the man widely credited as the inventor of the World Wide Web.

In his recently published memoir, This Is for Everyone: The Unfinished Story of the World Wide Web, Berners-Lee delivers a delightful and fast read—and a timely one. In this age of increasingly rich and powerful tech companies, Berners-Lee’s vision for the web remains fundamentally democratic: that everyone, anywhere, with access to what is now known as the internet, should have the ability to create and share information freely. It is no wonder that the word “patent” does not appear in the book’s index: TBL’s fiercely libertarian vision of decentralized infrastructure and an empowered online citizenry has been a cornerstone of his work from the 1980s to this day.

At the most fundamental level, TBL succeeded in realizing his vision. But the ongoing development of the web continues to be contentious. And in his book, TBL delivers a much more frank and open narrative than I would have anticipated.

Sure, there’s a fair amount of “wow, I had a meeting with the King” passages, as some readers have pointed out. But I found these to be more gleeful rather than self-indulgent. And, for the most part, the book faithfully recounts much of the travail that TBL encountered in his struggle to connect the scientists and researchers at CERN to various lists of resources and information.

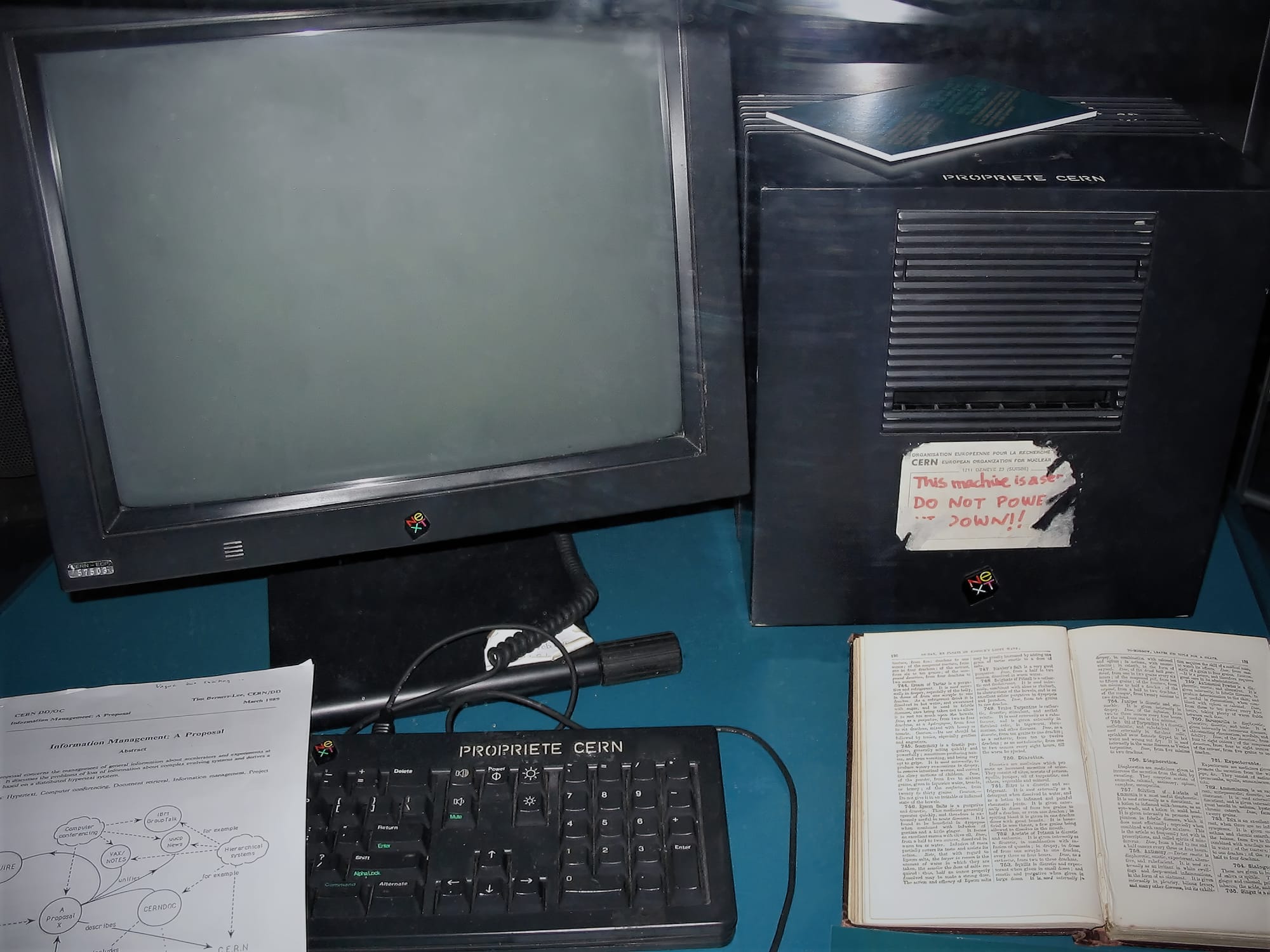

In the book, TBL recounts his how early effort of 1989, “Information Management: A Proposal,” garnered one of the most famously understated reviews ever, from his then boss Mike Sendall: “Vague, but exciting.”

But with encouragement, and a new workstation from NeXT (a new computer company founded by Steve Jobs that was running a version of the UNIX operating system) TBL began drafting the code for a server that would transmit pages (httpd), and for an early web browser (WorldWideWeb) that would enable those pages to be read.

From there, the events that would eventually establish the modern web accelerated at breakneck speed. By 1991, TBL had launched a new mailing list called www-interest, along with a counterpart aimed at the early developer community, www-talk. In 1993, the U.S. lifted all commercial restrictions on the early internet with the National Information Infrastructure Act, and the first browser to provide support for inline images, Mosaic, was released by the NCSA (National Center for Supercomputing Applications).

Visionary

But while TBL rightly deserves credit for designing the World Wide Web, a vision of networked information actually preceded him by many years.

I am a member of the PLATO generation—an early national network that began in the 1960s. Supported by the National Science Foundation at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and later licensed and further developed by the Control Data Corporation (CDC), PLATO had an emphasis on K-12 education. In the 1970s, with CDC’s engagement, a network of PLATO IV terminals was launched across the United States that introduced some of the most fundamental network technologies, including chat, messaging, email, message boards, newsgroups, and screen sharing for tutors and pupils.

While I was supposed to be using the terminals to learn algebra in a San Antonio school, I used PLATO to play Moria, an early multi-player D&D game, with other students stretched across the Central time zone who had levered their way into their schools’ computer labs after hours.

The design and formatting for the web, which we now take so much for granted, was also developed from work outside CERN. ViolaWWW, developed by Pei Yuan Wei while a member of the Experimental Computing Facility at UC Berkeley, was unabashedly based on the vision of HyperCard from Apple Computer, developed by Bill Atkinson.

HyperCard envisioned a series of stacked, interlinked cards. But what was missing was a means of sharing files across the early network. When Pei Yuan Wei encountered TBL’s early work, he immediately expressed interest in developing a new, graphical browser for X Windows. “Sounds like a good idea,” TBL responded on www-talk in December 1991. Four days later, Pei Yuan Wei announced the browser in the same forum.

The book also makes clear that TBL’s vision for the web was more expansive than its achievements. From the beginning, TBL perceived the web as a read-write medium and coded the ability to write web documents directly into his first browser, NeXT’s WorldWideWeb.

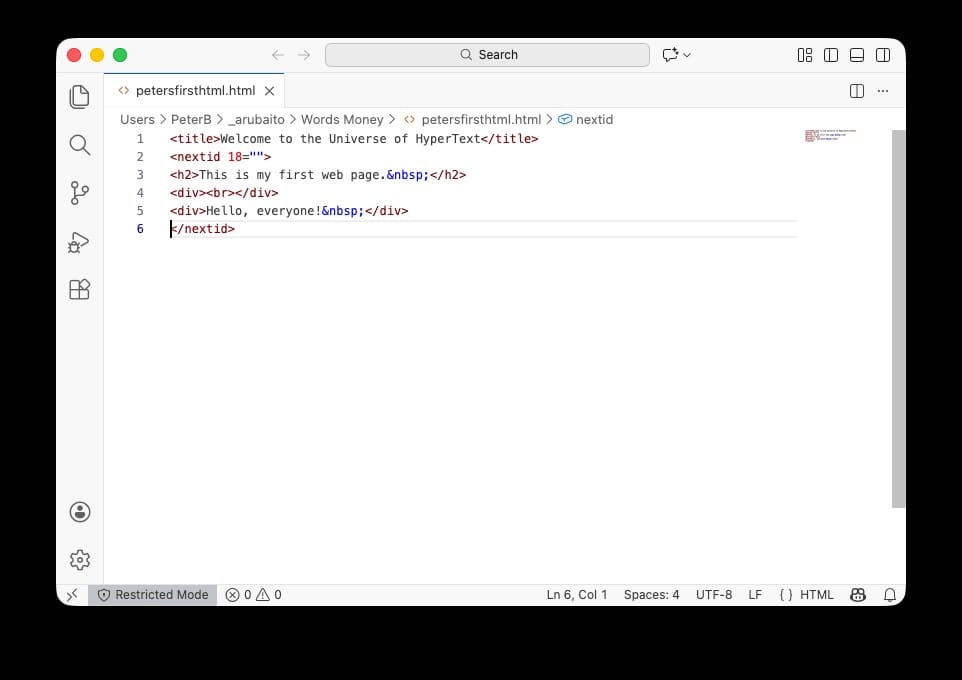

In 2019, to celebrate the web’s 30th anniversary, a small group of developers and designers gathered at CERN to rebuild the earliest browser. “At its heart, WorldWideWeb is a word processor… but with links,” the team wrote in a report. “And just as you can use a word processor purely for reading documents, the real fun comes when you write your own.”

Using their rebuilt browser, I was able to write my own first generation web page, whose source code looks like this:

But TBL also recognizes in the book that his vision of a participatory, democratizing web has only partially come to be fulfilled, and that sustaining that vision is an ongoing struggle.

“Wikipedia is probably the best single example of what I wanted the web to be,” TBL tellingly writes in the book, while noting that the software used to build Wikipedia—Wiki pages, developed by Ward Cunningham—was never patented because Cunningham never thought the concept was anything that anyone would want to—or perhaps have to—pay for.

This vision of a world where everyone across the world has an unencumbered ability to participate in online discourse equally, and with mutual respect, continues to drive TBL. Acknowledging that today’s web often prioritizes profits over people, TBL’s new project, Solid, is an effort to build a decentralized web of made up secure, private data stores, known as pods, that every individual can control, determining for themselves who—or more to the point, which companies—can access to their personal information.

Like his vision for the World Wide Web, Solid reflects a world in which individuals get to make informed choices for themselves and can participate in a network of sharing on their own terms. And while there have been some trials of the Solid concept, e.g. by the U.K.’s National Health Service, as well as some European investigations, such as the European Digital Identity Wallet, the project certainly faces some significant technical barriers: interchange protocols have to be agreed upon; standards for authentication need to be refined; and the software infrastructure necessary to support Solid Pods must be developed and made scalable.

And, of course, crucially, to be sustainable the project must secure some combination of individual, government, and corporate support.

This hits on perhaps the most important takeaway from reading This Is for Everyone—and something library and information professionals can certainly relate to: as unregulated AI companies spend billions on infrastructure and dealmaking, we the people must demand a role in crafting our information future, lest that future be determined solely by boards of directors and shareholders driven by profit. The book makes clear that the free exchange of ideas is not a birthright, but an exercise.

Peter Brantley is the Director of Online Strategy for the University of California Davis Library.